Parkinson's symptoms: What are the early signs of Parkinson's?

Overview: What does Parkinson's look like?

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive nervous system disorder that gradually reduces people’s ability to move. Parkinson’s disease gradually degrades the part of the brain that produces dopamine, a chemical in brain cells need to govern and control muscle movements.

Movement disorders are primarily how Parkinson’s is diagnosed, though Parkinson’s can also affect thinking, concentrating, mood, smell, and bowel movements.

While symptoms will vary from person to person, the average Parkinson’s patient will find it hard to control some movements, like hand tremors. Muscles may be stiff or difficult to move, necessitating small steps or writing in small letters. Reaction times slow down. People who are used to making fast movements like typing may find themselves going much slower. The range of movement decreases in some parts of the body. It may get hard to walk normally or even stay balanced. Standing up may get slower and harder to do.

Unfortunately, Parkinson’s is only diagnosed based on the movement symptoms, so the earliest signs of Parkinson’s only manifest when the disease has progressed far enough to start affecting muscle control and movement.

Key takeaways:

Parkinson's is a rare health condition that mostly affects older people but can affect anyone regardless of age, sex, race, or ethnicity.

Early signs of Parkinson's include hand tremors, reduced sense of smell, stiffness, hunching, fatigue, and smaller handwriting.

Serious symptoms of Parkinson's rarely require immediate medical attention, but complications such as falls, infections, and serious side effects of medications do.

Parkinson's is caused by a loss of nerve cells in the brain that produce dopamine. You may be at increased risk for developing Parkinson's symptoms if you have a relative with Parkinson’s disease, are older than 40, or have been exposed to certain toxins.

Parkinson's requires a medical diagnosis.

Symptoms of Parkinson's generally require treatment. They typically improve with treatment, but treatment does not slow the progress of the disease.

Treatment of Parkinson's may include Sinemet (carbidopa/levodopa), dopamine agonists, MAO inhibitors, anticholinergics, amantadine, physical therapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy, or deep brain stimulation.

Untreated Parkinson's could result in complications like falls, injuries, infections, aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, sleep problems, and medication side effects.

Save on prescriptions for Parkinson's with a SingleCare prescription discount card.

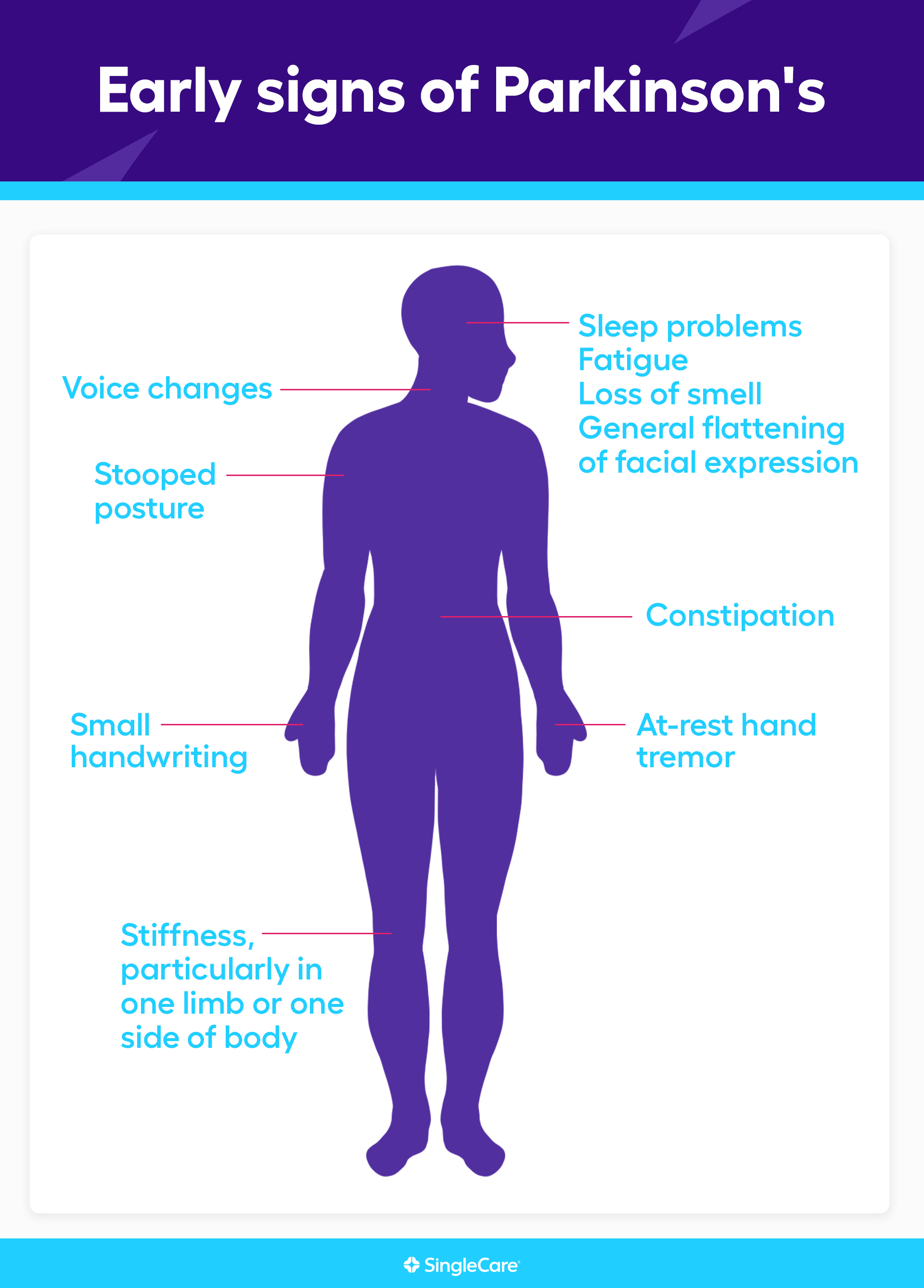

What are the early signs of Parkinson's?

Parkinson’s is only diagnosed when two movement disorders typical of Parkinson’s are present. Before that happens, non-motor and subtle motor symptoms may be a sign that the disease may be in its early stages. These early warning signs of Parkinson’s include:

At-rest hand tremor

Small handwriting (micrographia)

Loss of smell

Stooped posture

Stiffness, particularly in one limb or one side of the body

Sleep problems

Fatigue

Constipation

Voice changes, particularly talking more softly than usual

General flattening of facial expression

Other Parkinson's symptoms

The key Parkinson’s disease symptoms are:

At-rest tremor

Muscle rigidity

Slow movements (bradykinesia)

Gait problems

If bradykinesia and tremor or rigidity affect one limb or one side of the body, that is enough for a Parkinson’s diagnosis to be strongly considered. Additional features would need to be considered by the healthcare provider to finalize the diagnosis.

These motor symptoms can manifest as many different common symptoms:

At-rest finger movements like “pill-rolling”

Difficulty standing up from a chair

Difficulty turning over in bed

Difficulty opening jars or bottles

Muscle stiffness or rigidity

Slowness of movement

Slowed walking

Shuffling walk

Shortened arm movement when walking

Stooped posture

Difficulty turning around when walking

Freezing when walking

Small handwriting

Inability to tap fingers or feet rapidly on one side

Reduced voice volume

Slurred speech

Easy loss of balance (slow postural reflex)

Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s include:

Fatigue (58% of PD patients)

Anxiety (56%)

Leg pain (38%)

Insomnia (37%)

Urinary urgency (35%)

Drooling (31%)

Difficulty concentrating

REM sleep disturbances

Constipation

Loss of smell

Memory problems

Depression

Excessive daytime sleepiness

General pain

Loss of interest in daily life

Sexual dysfunction

Lightheadedness and dizziness

Difficulty swallowing

Restless legs

Nervousness

Trouble breathing

Excessive sweating

Taking no pleasure in anything

Sources:

Parkinson’s disease, StatPearls

Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis and treatment, American Family Physician

The Priamo Study: a multicenter assessment of nonmotor symptoms and their impact on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease, Movement Disorders

Parkinson's vs. ALS symptoms

Both Parkinson’s and ALS affect the brain’s ability to use the muscles in the body. Many of their symptoms overlap, but there are significant differences. People with Parkinson’s gradually lose the ability to coordinate muscle movement. They become slower, more rigid, and jerkier in their movements, but they don’t completely lose the ability to move their muscles. People with ALS lose the ability to send nerve signals to their muscles, so they gradually get weaker until they can’t move their muscles at all. The signature symptoms of Parkinson’s are at-rest tremors, muscle rigidity, and slow muscle movements. The signature sign of ALS is progressive muscle weakness that, in less than five years, leads to significant debilitation. People with Parkinson’s also have a wide range of non-motor symptoms, particularly psychiatric symptoms. Non-motor symptoms are less common in ALS patients.

|

Parkinson's |

ALS |

|

| Shared symptoms of Parkinson's and ALS |

|

|

| Unique symptoms of Parkinson's vs. ALS |

|

|

Sources:

ALS symptoms and diagnosis, ALS Association

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Lou Gehrig’s disease, American Family Physician

Stages of Parkinson's: How can I tell which one I have?

Healthcare professionals classify Parkinson’s disease based on the severity of the symptoms. They use symptom rating scales, namely the Hoehn & Yahr scale or the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS-MDS).

The Hoehn & Yahr scale groups these symptom scores into one of five disease progression stages, each marking more severe symptoms and disability.

The UPDRS-MDS used by movement disorder specialists simply gives a single score from 0 to 199, with 0 meaning no symptoms and 199 meaning severely disabled. No “stages” are used.

Remember, these scales and any “stages” the scores are grouped into simply measure the severity of the symptoms—not the underlying disease itself. Because the symptoms worsen over time, people with Parkinson’s and their caretakers should understand how the symptoms worsen and what to expect in the future. However, each person shows a different progression of symptoms, so get evaluated by a doctor to determine what stage the disease is in.

When to see a doctor for Parkinson's symptoms

See a doctor for medical advice if you’re worried about having any early signs of Parkinson’s, particularly any of the muscle movement symptoms. Remember: one of the defining features of Parkinson’s is that the movement problems start in one limb or on one side of the body only.

Symptoms are the only way to diagnose Parkinson's disease. There are no blood tests, urine tests, imaging tests, or biopsies that can confirm the diagnosis. There must be symptoms within at least two of the primary diagnostic criteria: at-rest tremor or rigidity, along with slow muscle movements. Gait problems typically come later. A thorough medical history is needed to rule out other causes, such as prescription drugs. A physical will be performed, and if other causes are suspected, an MRI or lumbar puncture can help rule them out. In the end, a definitive diagnosis of Parkinson's disease can be aided by trialing levodopa treatment. If symptoms improve, the diagnosis is supported.

If you suspect you have Parkinson’s, but the symptoms aren’t sufficient for a healthcare professional to diagnose Parkinson’s, then keep a symptom diary. As symptoms develop or worsen, be prepared to show the symptom diary to a healthcare provider.

Complications of Parkinson's

The most serious complications of Parkinson’s are related to disability or dopamine treatment. These include:

Falls and injuries

Infections

Aspiration pneumonia due to swallowing problems

Malnutrition due to swallowing problems

Orthostatic hypotension (dizziness when standing up)

Sleep disorders

Sleep attacks and excessive daytime sleepiness

Vigorous dreams that may result in injury (REM-sleep behavior disorder)

Involuntary movement disorders (dyskinesias) caused by dopamine treatment

Severe and life-threatening involuntary movements due to treatment (dyskinesia-hyperpyrexia or dyskinetic storm)

Psychosis due to treatment

Impulse-control problems due to treatment

Sources:

Emergencies and critical issues in Parkinson’s disease, Practical Neurology

Parkinson’s disease and the frequent reasons for emergency admission, Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment

How to treat Parkinson's symptoms

Parkinson’s symptoms do require treatment. Unfortunately, there is no curative treatment for the underlying condition. Since Parkinson’s patients have a shortage of the neurotransmitter dopamine, standard therapy involves replacing dopamine using the combination drug carbidopa/levodopa. Some patients may be started on drugs that mimic dopamine, such as pramipexole or ropinirole.

Amantadine or anticholinergics can treat mild cases where the tremor is the main issue. MAO inhibitors are another possible early treatment.

Conversely, if COMT inhibitors are used, it is typically later in the treatment course, to facilitate a better response to carbidopa/levodopa.

Other drugs can be prescribed to treat individual symptoms, but healthcare professionals are reluctant to pile up drug treatment due to side effect concerns.

Treatment will also involve physical therapy. Other treatment options include speech therapy and occupational therapy. As the disease progresses, doctors may implant electrodes in the brain to help regulate brain signals. They are fired by a device implanted somewhere else in the body. Called deep brain stimulation, these electrical impulses may help control movement symptoms.

Living with Parkinson's

Parkinson’s is a progressive disease that can produce profound disabilities. There is no set timeline, but symptoms do get worse. Patients, family members, loved ones, and caregivers must be aware of the progress of the disease and plan for future disabilities. There are ways to live a full life even with Parkinson’s symptoms. The first order of business is safety. It’s important to make modifications to the home and be aware of nearby services. The second order of business is just plain living. Various tools can help people with daily activities when they become difficult.

Most importantly, see a neurologist for early diagnosis

Parkinson’s symptoms can be managed with medications, but only a neurologist can definitively diagnose and treat Parkinson’s. It’s a challenging diagnosis, but the diagnosis simply points the way forward. Treatment does help, as does assistive technology, physical therapy, and support groups.

FAQs about Parkinson's symptoms

What age does Parkinson’s start?

Parkinson’s can strike at any age, but the incidence gradually increases after age 40.

How long do people with Parkinson’s live?

There is no set timeline for the progress of Parkinson’s symptoms. In one study, people lived anywhere from two to 37 years after a diagnosis. The most meaningful risk factor for a short progression of the disease is age. Younger people live longer after a Parkinson’s diagnosis than older people. That makes sense. The average age at which people die from Parkinson’s is 81.

What does Parkinson’s smell like?

Recent Parkinson’s research has found that there is a unique scent associated with people with the disease. The scent comes from an increase in sebum, which is a waxy, oily substance that protects and moisturizes the skin. The Parkinson’s scent is not noticeable to most people, but it may be an important biomarker in the diagnosis of the disease.

Is loss of smell a symptom of Parkinson’s?

Parkinson’s can affect the sense of smell. A reduced sense of smell or loss of smell is a common early symptom of Parkinson’s.

What’s next? Additional resources for people with Parkinson’s symptoms

Test and diagnostics

10 early signs, Parkinson’s Foundation

Parkinson’s disease, StatPearls

Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis and treatment, American Family Physician

The Priamo Study: a multicenter assessment of nonmotor symptoms and their impact on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease, Movement Disorders

Treatments

Emergencies and critical issues in Parkinson’s, Practical Neurology

Parkinson's disease, American Family Physician

Parkinson’s disease, StatPearls

Scientific studies and clinical trials

New clues on why some people with Parkinson’s die sooner, American Academy of Neurology

Parkinson’s disease and the frequent reasons for emergency admission, Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment

More information on related health conditions

ALS symptoms and diagnosis, ALS Association

Chad Shaffer, MD, earned his medical doctorate from Penn State University and completed a combined Internal Medicine and Pediatrics residency at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He is board certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American Board of Pediatrics. He has provided full-service primary care to all ages for over 15 years, building a practice from start up to over 3,000 patients. His passion is educating patients on their health and treatment, so they can make well-informed decisions.

...Related Drugs

Related Drug Information

Recetas Populares

SingleCare es un servicio de descuentos para medicamentos recetados que ofrece cupones gratuitos para miles de medicamentos. Puedes usarlo aun si tienes seguro, Medicare, Medicaid o no, pero no se puede combinar con el seguro.

SingleCare ofrece transparencia al mostrar los precios de medicamentos para que puedas comparar descuentos en farmacias cerca de ti. Visita singlecare.com para encontrar descuentos en medicamentos, información útil sobre tu receta médica y recursos que te ayudan a tomar decisiones informadas sobre tu salud.

Los ahorros en recetas varían según la receta médica y la farmacia, y pueden alcanzar hasta un 80% de descuento sobre el precio en efectivo. Este es un plan de descuento de recetas médicas. NO es un seguro ni un plan de medicamentos de Medicare. El rango de descuentos para las recetas médicas que se brindan bajo este plan, dependerá de la receta y la farmacia donde se adquiera la receta y puede otorgarse hasta un 80% de descuento sobre el precio en efectivo. Usted es el único responsable de pagar sus recetas en la farmacia autorizada al momento que reciba el servicio, sin embargo, tendrá el derecho a un descuento por parte de la farmacia de acuerdo con el Programa de Tarifas de Descuento que negoció previamente. Towers Administrators LLC (que opera como “SingleCare Administrators”) es la organización autorizada del plan de descuento de recetas médicas ubicada en 4510 Cox Road, Suite 11, Glen Allen, VA 23060. SingleCare Services LLC (“SingleCare”) es la comercializadora del plan de descuento de prescripciones médicas que incluye su sitio web www.singlecare.com. Como información adicional se incluye una lista actualizada de farmacias participantes, así como también asistencia para cualquier problema relacionado con este plan de descuento de prescripciones médicas, comunícate de forma gratuita con el Servicio de Atención al Cliente al 844-234-3057, las 24 horas, los 7 días de la semana (excepto los días festivos). Al utilizar la aplicación o la tarjeta de descuento para recetas médicas de SingleCare acepta todos los Términos y Condiciones, para más información visita: https://www.singlecare.com/es/terminos-y-condiciones. Los nombres, logotipos, marcas y otras marcas comerciales de las farmacias son propiedad exclusiva de sus respectivos dueños.

Los artículos del blog no constituyen asesoramiento médico. Su propósito es brindar información general y no sustituyen el asesoramiento, diagnóstico ni tratamiento médico profesional. Si tiene alguna pregunta sobre una afección médica, consulte siempre a su médico u otro profesional de la salud cualificado. Si cree tener una emergencia médica, llame inmediatamente a su médico o al 911.

© 2026 SingleCare Administrators. Todos los derechos reservados

© 2026 SingleCare Administrators. Todos los derechos reservados